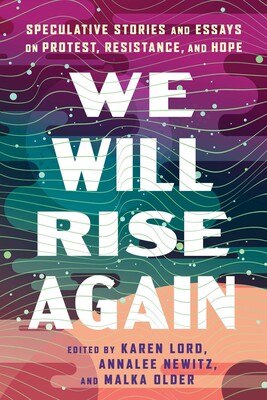

When I first heard about the We Will Rise Again anthology, somehow I immediately thought of Octavia’s Brood (edited by adrienne maree brown & Walidah Imarisha, AK Press 2015), Mothership (edited by Bill Campbell & Edward Austin Hall, Rosarium Publishing 2013), So Long Been Dreaming (edited by Nalo Hopkinson & Uppinder Mehan, Arsenal Pulp 2004), and even books like Dark Matter (edited by Sheree Renée Thomas, Warner Aspect 2001) and the too often overlooked or forgotten Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction (edited by Grace L. Dillon, University of Arizona Press 2012).* Did you each have precursors – books, authors, or editors that were important or inspirational, or that you see as tied in some way to this anthology? Or was this book very independent of those kinds of connections?

Malka: Octavia’s Brood was also the first thing I thought of when Annalee and Karen told me the idea; we reached out to adrienne and Walidah immediately and told them about the project, and once we got close to completion we asked them for an interview, and it was an amazing and humbling conversation—they had so many insights in an off-the-cuff interview, we were really pleased to be able to include it in the book.

Karen: We are so indebted to Octavia’s Brood. Our interview with them is fittingly at the start of the book, helping us to lay the foundation for everything that comes after.

Annalee: Other than Octavia’s Brood, which has been a huge inspiration, I was thinking about the hopeful science fiction anthology Hieroglyph, which was put together by ASU. What I liked about Hieroglyph was that it was explicitly about trying to imagine ways of solving big problems like climate change and renewable energy. Each author was paired with a scientist who could help make their solutions plausible and maybe even do-able in real life. I wondered what it would be like to have an anthology where we took social science and activism as seriously as Hieroglyph took science. And that’s why I knew from the jump that we would need activists and community leaders involved in this project; their knowledge and wisdom is so valuable, and deeply important for our storytelling about protest and resistance.

I’m always fascinated by collaborations, because not everyone works well (or plays well) with others. Not only this, but even in the conceptualization stage, so often creatives think of a project as “theirs” as opposed to something they can create with someone else. How did this project come about, what was the initial inspiration or process for deciding to do it?

Karen: Malka hosted the Sparkle Salon podcast where I said something that inspired Annalee to put together the concept for the anthology. Annalee approached me to co-edit, and I immediately said yes. As the magnitude of the project became more evident, I suggested to Annalee that we invite Malka as a third editor, and then Malka joined us. Perfect circle! But I always say it’s primarily Annalee’s anthology because they were the key instigator.

Annalee: I always say it was our collective action that brought the anthology together! I am so grateful that Karen and Malka wanted to join me and make this book happen. Truly it would not exist without all our ideas and hard work.

Malka: I was so thrilled when Annalee and Karen asked me to join them, because the idea and project are amazing and also because I love working with them. I had always enjoyed our conversations during the Sparkle Salon, as well as whenever we met at events or on virtual panels. And, to address the broader question a bit: we all knew this would be a lot of work, and we would need each other, both for the actual getting-it-done bits, and for the moral and psychological support of doing something we all believed worthwhile. And it’s wonderful to work with other writers – not just the editors, the contributors, too. There was the project of making the book and there was the way it contributed to the ongoing project of community building. There’s so much we can’t control in the publishing industry, and connecting, respecting, uplifting each other is both important and often its own reward.

How did you work together—who did what, and did things go smoothly, or were there adjustments that had to be made along the way?

Karen: All three of us are busy people, and the project began during the waning years of the pandemic when we were all stretched a bit thin by incessant crisis. My approach from the start was to be brutally honest with my “noes” if I felt I couldn’t handle something, and also to enthusiastically volunteer when I knew I had the time and skills to do the task well (or at least adequately!). Annalee and Malka are fantastic to work with because they are both frighteningly competent and remarkably free of ego. It was easy to be completely open with them and work together to find solutions.

Malka: Our virtual meetings were such a balm that we would often stay on chatting long after getting done what we needed to get done, or even schedule catch-up meetings just to see each other’s faces. It made such a difference to the project—which, let’s be real, was a lot of work over a long period of time when we were all really busy with other things—that it was such a pleasure to work together.

Annalee: Yes to all of this. I feel like we started this project as friendly colleagues and now we’re friends who built something wonderful together—with the help of even more friends! Whenever I was feeling overwhelmed, Karen or Malka could step in and pick up the slack—and vice versa. Plus the authors and activist contributors kept my spirits up when times were grim.

What did you learn or discover, or what surprised you, if anything, in the process of putting this book together?

Karen: One of the themes embedded in the anthology is that although art may be a response to suffering, art does not have to arise from suffering. Many of us had ongoing challenges in our lives, and of course the world was constantly demonstrating fresh horrors. But the process of putting the book together was so rewarding, even when it was hard work, that it felt like the opposite of suffering. There was joy. There was love. It didn’t surprise me exactly, because I always felt that was possible. But I needed the confirmation. I get angry at people who make it hard for creatives to create because they truly believe in the suffering artist myth, or just use it as a lazy excuse to be unkind to people.

Malka: Very much agree. It was really eye-opening to talk to the activists and hear from them about history and context that I didn’t know, and especially hope. I think a lot these days about the US war on Iraq and how there were these huge demonstrations and marches against that aggression, and I had, perhaps without overly analyzing, become somewhat cynical about what I saw as a lack of impact from that, so it was incredible to hear L. A. Kauffman, one of the organizers, talk about the long game, the other impacts we didn’t see, the way it connected people, what was learned from the action. It was very powerful to hear from her and the other activists who spoke to us about how they keep their hope up even as the tides of oppression rise and fall.

Annalee: I think the most surprising thing of all was that a big publisher picked it up and gave us enough of an advance that we could pay all our contributors professional rates, and pay ourselves as editors, too. I never thought that would happen. Having the Saga team behind us, and our incredible editor Sareena Kamath—it’s amazing. This isn’t usually the kind of book that gets institutional support from one of the Big Five. I feel unbelievably lucky.

What were the biggest challenges to making this book happen—whether in collaboration or publishing or gathering materials or something else—and how did you deal with those challenges?

Karen: I’m not sure if this counts as a challenge exactly, but I genuinely wasn’t sure who was going to publish it. I mean, that was a challenge for the agents, not for me, but still! A big book of stories, essays, and interviews. Why didn’t we try to keep it simple? What category will this be eligible for when it comes to awards? Anthology? Related work? But we knew what we wanted it to be, and we didn’t compromise.

Malka: An important challenge, and maybe a good lesson too if I can overlap with the previous question, was keeping up the momentum and the process even when it wasn’t at all clear that the book would ever get written or published. We weren’t sure at the beginning if we would find a grant to get started, or do crowdfunding, or manage to get a traditional publisher. There was a long period after we solicited stories of waiting to see what we would get, knowing some people would have to drop out of the project for whatever reason. We managed to do this virtual conference, with support from Arizona State University Center for Science and the Imagination (where I work part time) to get the potential writers together with activists, and we knew we were asking people to put time in with very little guarantee of what it would come to. As long-form authors we are, I think, all at least somewhat comfortable with the idea of incremental progress on big projects without knowing what they’ll look like at the end or whether anyone else will read them, but doing it collectively was a good reminder of the sort of faith and determination that it takes to keep moving forward step by step.

How were selections made, and were there pieces you had hoped to include which didn’t make it into the final book for one reason or another?

Karen: We expected and prepared for some writer attrition. We had a few authors who we’d hoped would have been able to contribute a story, but who ended up not being able to for the usual reasons (time, muse, etc.). However, out of the submitted pieces, none were rejected. Perhaps we curated our author list extremely well (of course!). But there were other factors. Requiring writers to have first-hand knowledge, or else talk to real-life activists with that knowledge. Having the virtual conference with presentations from movement leaders. Maybe that preparation before writing made a difference.

You are all respected fiction writers, and readers may or may not know but you all are also respected nonfiction writers. How does having written and published fiction and nonfiction change or impact your perspective or process when it comes to selecting pieces for an anthology like this?

Annalee: I think all of us agreed from the beginning that this was going to be a book that is heavily informed by real-world experience. But we didn’t want to give readers simple allegorical stories, or facile “this is the future of X political movement from the real world.” We wanted to demystify the process of using our imaginations to solve real-world problems, to offer readers a roadmap so they could do this in their own lives. That’s why we have nonfiction and interviews alongside our fiction. The idea is to show readers how we can use our imaginations to engage with vital social issues, to change people’s minds, and to expand our own understanding of what’s possible. Our hope is that this book can be educational, a teaching tool for movement leaders and anyone else who seeks community and hope.

I apologize for this question, because I know it annoys and traumatizes a lot of people. However, we have finite space! And we can’t get into each entry in depth! So: each of you please pick one entry, whether an essay or piece of fiction or something else, and tell us a bit more about it, just to give readers a closer or more specific taste of what’s in store.

Annalee: I worked a lot with Abdullah Moaswas on his story “Kifaah and the Gospel,” which is about what happens to the Palestinian people after Israel relocates its citizens to a distant planet where they can rule unopposed. He submitted the story in late 2023, and many of the satirical details he’d included—like a weaponized AI called “Gospel,” and the deliberate erasure of Palestinian history online—began to come true as the genocide continued. As the war went on, and we started working on edits, what emerged out of the story was a profound and grounded sense of hope. Abdullah has written about the meaning of food in his academic work, and he incorporated that into the story, imagining how Palestinian people would cleanse the war-ravaged land by encouraging the growth of native plants used in Palestinian cooking. I can’t tell you how much it meant to me to read this story about the survival of Palestine—especially the survival of Palestinian traditions and foodways—in this dark time. This story balances perfectly between wrathful satire and sincere hope.

Karen: I want to highlight “Other Wars Elsewhere” by R.B. Lemberg. It’s set in a Europe-inspired, contemporary fantasy world and it deals with something I understand well as someone from the Caribbean—the concept of crisis fatigue, the struggle of trying to help with big, collective crises that linger and multiply while also managing personal crises that may seem not as important as war and disaster, but may yet be as wearying, and even as deadly. Without giving spoilers, there’s also a poignant portrayal of how we need both help and magic to “knit up the raveled sleeve of care…” that is, to mend our trauma and heal ourselves for the next battle. My heart was deeply touched by this story: the concept, craft, and prose all sing together.

Malka: “Where Memory Meets the Sea” made me cry, it is so beautiful and powerful on what is lost in exile and the power and hope of community.

The tag line for We Will Rise Again is “Speculative stories and essays on protest, resistance, and hope.” Why did this specifically need to be a book of speculative works, what does speculative work do which perhaps is important or different from works we might not call “speculative”?

Karen: You need the speculative if you’re going to imagine a different world.

Annalee: Honestly, it’s as simple as that. Realism and news reporting will take you only so far. We need to start working together on new narratives, new ways of imagining community and justice. Speculative storytelling is a good start.

Malka: Yeah, all of this. Particularly for structural, paradigmatic change—we need to not just imagine along the spectra and variables we have, but imagine new shifts. Speculative thinking is vital for that—for being free to imagine things that other people will say is impossible – I’m not going to repeat the Le Guin quote, but that—and also, often, because setting a story in the far future or a fantasy world gives readers the distance to see their own situation differently.

You each have a lot of work out in the world. Tell us about one project of your own, separate from this book (short fiction, essay, book, whatever you like!) that you feel most relates to We Will Rise Again.

Karen: I’d choose Unraveling. Two questions lie at the core of the novel: how do you change an unjust city? how do you redeem an intolerant soul? The answer is: you have to build something new, and become someone new.

Annalee: I’d say probably my nonfiction book Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind. I argue in that book that one way to deescalate psychological warfare and toxic narratives is by changing the subject and lifting up new stories. It’s sort of the opposite strategy of “debate me, bro.” That’s a dead end. True cultural transformation begins when we say, “Hey, listen to something else now. A tune we’ve never heard before. Maybe we can sing it together.”

Malka: I don’t know, the Centenal Cycle trilogy (starting with Infomocracy) is more overtly political, but it’s also with some exceptions largely focused on governance rather than activism and resistance, and my current series, the Investigations of Mossa and Pleiti (starting with The Mimicking of Known Successes) is also very much about imagining alternatives to the structures and trends of right now.

Is there anything else you’d like readers to know about you as individuals or as a team, your work, or We Will Rise Again?

Annalee: The book comes out Dec. 2, and we’ll have an in-person launch of the book that evening at Booksmith in San Francisco, followed by several virtual events. We’ll have a full list of dates and links for those events very soon.

*Note: this is not by any means an exhaustive list of books that came to mind… but these are some cool books! Check them out if you haven’t, and then find more like them. : ) —Arley

Barbadian writer and editor Karen Lord is the author of Redemption in Indigo, which won the 2011 William L. Crawford Award and the 2012 Kitschies Golden Tentacle (Best Debut), and was nominated for the 2011 World Fantasy Award for Best Novel. Her other works include Unraveling, the second novel in the Redemption series, and The Best of All Possible Worlds, The Galaxy Game, and The Blue, Beautiful World (longlisted for the 2024 Women’s Prize for Fiction) in the Cygnus Beta series. She also edited New Worlds, Old Ways: Speculative Tales from the Caribbean, and coedited We Will Rise Again: Speculative Stories and Essays on Protest, Resistance, and Hope with Annalee Newitz and Malka Older.

Malka Older is a writer, sociologist, and aid worker. A faculty associate at Arizona State University’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society, she teaches on the humanitarian-development spectrum and on predictive fictions, and is an associate researcher at the Centre de Sociologie des Organisations. She’s spoken at venues including SXSW, the Personal Democracy Forum, the FWD50 conference, and the Hamburg International Summer Festival on topics such as democracy, data, narrative disorder, and speculative resistance. Older’s The Mimicking of Known Successes was named a best book by Library Journal; its sequel, The Imposition of Unnecessary Obstacles, was just published. Older’s sci-fi political thriller Infomocracy was named a book of the year by Kirkus Reviews, Book Riot, and The Washington Post. She is also author of Null States and State Tectonics, the creator of Ninth Step Station, and lead writer for the licensed sequel to Orphan Black. She’s written opinion pieces for The New York Times, The Nation, and Foreign Policy.

Annalee Newitz writes science fiction and nonfiction. They are the author of four novels: Automatic Noodle, The Terraformers, The Future of Another Timeline, and Autonomous, which won the Lambda Literary Award. As a science journalist, they are the author of Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age and Scatter, Adapt and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction, which was a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize in science. They are a writer for the New York Times and elsewhere, and have a monthly column in New Scientist. They have published in The Washington Post, Slate, Scientific American, Ars Technica, The New Yorker, and Technology Review, among others. They are the co-host of the Hugo Award-winning podcast Our Opinions Are Correct, and have contributed to the public radio shows Science Friday, On the Media, KQED Forum, and Here and Now. Previously, they were the founder of io9, and served as the editor-in-chief of Gizmodo.