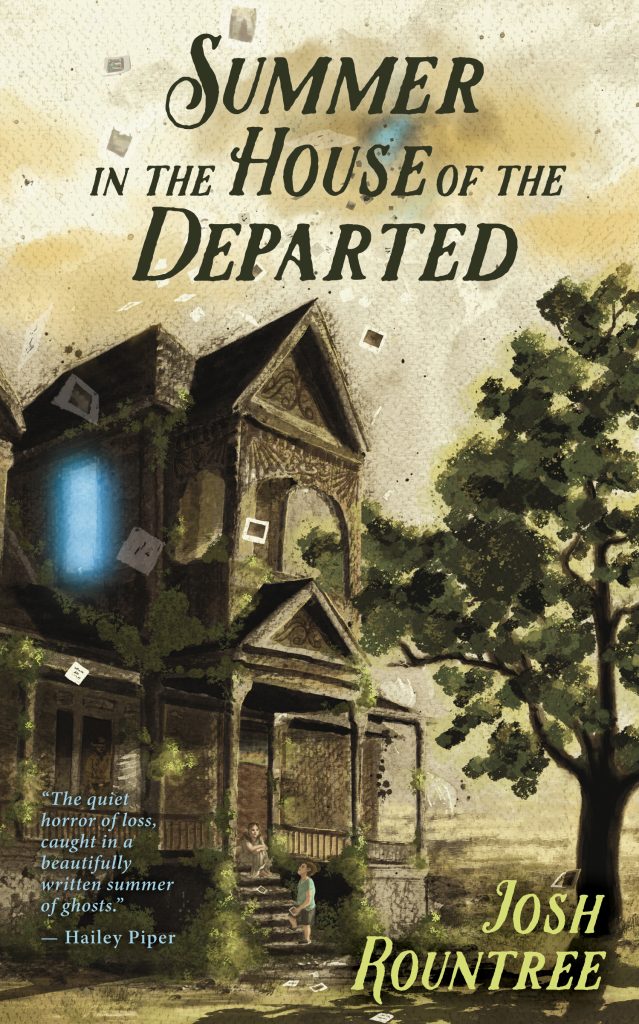

August 26 sees the release of Summer in the House of the Departed, the new novella from Josh Rountree, a Texas novelist and short story writer. What follows is a sneak peek for you, dear reader. You can buy your very own copy from us right now.

For now, read on.

The summer my grandmother disappeared, taking an entire Texas town with her, she showed me photos of her ghosts.

She placed the photos on the kitchen counter, snapping each one against the shell-pink Formica like playing cards. Some of the more interesting ones she tapped with her finger to make sure I took special notice. “That one there was taken out near Sterling City.”

“You took it?”

“No, a woman lives there took it. Sent it to me.”

It was a Polaroid with Thanksgiving 1978 written along the bottom. A little girl with a long-sleeve shirt and blue jeans tucked into red cowboy boots sat in a high-backed wicker chair, laughing, and pointing back at the camera. Blue light blossomed out from behind the chair in a vaguely humanoid shape, and two tendrils wrapped around the girl like transparent arms, giving her a hug.

“Lady who sent this say the girl is her daughter, and the ghost is her late mother.. She died that summer before. The old woman used to favor that chair. Her ghost started making a whole lot of racket around the house anytime somebody sat in it. This was a few years back, so might be she’s moved along by now.”

“What kind of racket?”

“Oh, just knocking on walls and stomping around. I recorded it. It’s on one of my cassettes.”

I wasn’t sure I wanted to hear it. The thought of dying and being bound to the real world while everyone carried on around you was more frightening to me than the ghosts themselves. If I had to die, I figured I’d rather go someplace else.

Granny filled an ashtray full of lipstick-stained cigarette butts while we talked our way through her stack of photos. Some she’d taken herself, others she’d received from people familiar with her reputation. Most of the photos showed smiling people with circular splotches above their heads, or streaks of light cutting across the image. Maybe the camera captured a bug. Maybe it was a trick of the light. Others were harder to explain, like the crying woman floating above a glassy lake, draped in a long white dress, arms outstretched.

Granny put down a second photo of the same floating woman, same position, like it was taken immediately after the first, except this time the woman’s dress was stained a deep red and she had the head of a horse. Her body was soft around the edges, like the camera had moved before the image could resolve.

“This one shows La Llorona. You remember the story I told you?”

“Yes, I know that one.” I stared at the picture. The horse woman’s lips were curled back around her flat teeth in a way that made it look like she was smiling.

“Might not ought to show you some of these.”

“Why not?”

“They’re liable to keep you up with nightmares.”

“Can I see the ones they took here?”

“Let’s save those for another time.”

Various people had taken photos in Granny’s house, both before and after she moved here, and she kept them in a cigar box in her desk, stacks of them bound with rubber bands. She’d always been happy to show me the rest of her photo collection, no matter how terrifying, but so far, she’d never been inclined to show me those in the cigar box.

I wasn’t sure why she thought they would frighten me more than the others. More than her house itself.

The place was thoroughly haunted.

That’s why she’d moved there in the first place.

Ghosts bled out from the margins of that old house, and I made friends with a few of them. Like thin gray memories they clung to the undersides of coffee tables and dwelled in the narrow space between the guest bed and the wall. In the nighttime, I’d peer over the edge of the mattress at their dull forms and whisper my secrets to them. They wouldn’t respond, but I judged their interest in the way their eyes never wavered from mine.

In the daylight they were like half-erased pencil marks against the windows and the walls, often escaping notice and more easily forgotten, but still grasping at whatever reality they called their own.

Among my favorites was the ghost of a girl about my age whom I’d decided to call Shirley. She wore an old-style dress I couldn’t place in time, and she lingered at my grandmother’s bookshelves, drawing the outline of her fingertips across the spines of the books. The raspy sound of her fingers running against the paperbacks was the only noise she ever made. When she settled on one, I’d read it aloud to her. Frequently it would be We Have Always Lived in the Castle, but today it was Something Wicked This Way Comes, and I believe she picked this one because I’d told her it was my favorite.

We passed most mornings this way, me a pudgy boy in beat-up tennis shoes and brown corduroys, my hair buzzed down in what they used to call a summer cut, and her, little more than a silver outline of the person she used to be, but with blue eyes that had never entirely released their hold on life.

My grandmother often watched us from the doorway; Granny was wraith-thin and hollowed by cancer, a wreath of cigarette smoke spinning over her head. She was only in her mid-fifties, which seemed appropriately old for a grandparent when I was eight, but shockingly young now that I’m chasing that age myself.

One morning, my grandmother’s research assistant arrived wearing loose jeans and a blouse, lugging a legal box full of paperwork, blonde hair knotted up on top of her head and sunglasses sliding down the end of her nose. Beverly was an English major at Angelo State with an eye toward folklore and the supernatural, and her whirlwind arrival blew the ghosts to hidden corners of the house. I’d learned the summer before that despite her interest in ghosts, Beverly couldn’t see the ones living here. She struck me as too energetic, too alive for the ghosts to reveal themselves.

I wasn’t sure what that said about me.

“Hey kid, what are you reading?” Beverly sat the box on the table and gave me a hug. I showed her the paperback in my hand. “I like that one,” she said. “But I like his science fiction stuff better.”

My grandmother greeted Beverly wearing an orange polyester pantsuit and the wig she wore whenever we left the house, or when company called. She dug through the papers Beverly had brought, turquoise bracelets clattering together on her wrists. She clenched a lit cigarette between her teeth when she spoke. “Any accounts here from primary sources?”

Beverly settled into a chair at the dining room table, where my grandmother had already spilled the paperwork across the surface in untidy stacks. “Not much. Nothing that would be new to you, anyway. But there’s some good general info about the time period, and a lot of quotable speculation over the years of what CROATOAN might mean.”

“Thank you, honey. Looks like some good stuff.”

“I also found some stories I don’t think you’ve referenced yet that might add color and corroboration. Small towns in California and Ohio that disappeared around the turn of the century. And this one here in Kansas, back in the fifties.”

Beverly slid a paper-clipped bundle of materials toward my grandmother.

“You’re talking about Ashley, Kansas?”

“Yes. Earthquake, fire from the sky. A lot of creepy calls to the cops about the dead coming back for a visit. And then everybody in the whole town just disappeared. There are a couple of phone numbers written down there. People who lived nearby when it happened. I got a hold of them, and they’re willing to talk to you.”

“This is good work. I’ve heard that story before, but nothing as detailed as this.”

“There’s talk of a hole in the sky,” said Beverly. “Maybe it connects to another dimension? That supports a scientific answer to this mystery, don’t you think?”

“Might be it does,” said my grandmother. “Either way, it’s interesting.”

I huddled underneath the table like one of the ghosts, hungry for scraps. I often learned more about what Beverly and my grandmother were researching when they forgot I was there. Shirley attached herself to the underside of the table too, a swirling mass with shining eyes, head cocked to the side like she was listening. We lazed there together, lulled half asleep by the heat and their voices.

“Another universe bumping up against this one is the only rational explanation, isn’t it?” Beverly took a seat at the table and tapped her shoe nervously against the floorboards. Shirley drifted close, grasped at the cuff of Beverly’s blue jeans with smoky fingers. Shirley had that dusty, moldering smell that many of us associate with long afternoons spent digging through forgotten bookstores, and I would carry that with me through life as the scent of my grandmother’s house.

“Why do you assume there’s a rational explanation?” my grandmother asked.

“There has to be, right?”

“There has to be an explanation,” my grandmother said, “but no reason it has to be rational.”

Granny wrote nonfiction books about the supernatural, and her latest project was about the Roanoke colony. I’d read about what happened there. As soon as I was old enough to sound out words, my grandmother loaded me down with books about aliens, bigfoot, ghosts, trolls living under bridges, portals to fairy kingdoms, doomsday cults, and by comparison, more prosaic mysteries like the story of Roanoke. I knew Roanoke was a colony of early American settlers who had disappeared in the late fifteen hundreds, leaving no clue to where they’d gone, except the word CROATOAN cut into the bark of a tree. Most historians figured they’d either been killed by natives or assimilated into one of their tribes, but such an enduring mystery was bound to elicit supernatural speculation as well.

I peered out from underneath the table, spying on them like another forgotten ghost.

“If you throw out science, how can you hope to figure all this out?” said Beverly. “That’s crazy, right?”

Before Granny moved here, before she got sick, she taught high school. English 101. Both levels of Spanish. She was accustomed to questions and reveled in learning. So, she accepted Beverly’s challenge in the spirit it was intended.

Granny smiled, struggled with the striker on her lighter as she started another cigarette.

“I don’t throw out science, honey,” she said. “And I don’t doubt there’s some rational outcome for what’s going on that you’d accept in those terms, if you had a textbook in your hands that codified it. But that won’t ever happen. Science won’t provide you that answer. You know why? Science is too proud. Science won’t dig deep enough. I’ve read reams of evidence on the supernatural, including your good work here. Testimonials by credible folks with no reason to lie. Photos. Recordings. Objectively provable psychic phenomena. Do scientists consider these things? Not many of them. Not if they value their reputation. No quicker way to get shunned by academia than admit you believe in ghosts and goblins. And that’s a shame. Because science is supposed to consider all evidence, isn’t it? How accurate can your finding be on a matter if you pretend a good bulk of evidence just doesn’t exist?”

“I don’t know,” said Beverly.

“Well, they don’t either. What I’m saying, girl, is all that stuff we call the supernatural is a natural part of science. You just can’t study it under a microscope or swirl it around in a test tube.”

“You know I love folklore,” said Beverly. “Stories. But there must be some real-world answer for these sorts of disappearances, right? These people aren’t being stolen away by fairies.”

“You’re sure of that?”

Beverly grinned, chewed at her bottom lip as she tried to figure out if Granny was joking. Tried to ready some sort of logical argument if she wasn’t. The genuine delight on her face, and the way she drew her hair back through her fingers when she was thinking intently, made something flutter in my stomach. She smelled like coconut shampoo and sunshine. Like she lived on a tropical beach and not in the same forsaken land as the rest of us. Beverly belonged someplace else. Someplace better. She was beautiful, and I suppose I had a crush on her, but my eight-year-old self wouldn’t have understood it in those terms.

“You know I’ve experienced things too?” said Granny. “Not to mention there’s ghosts all over this house. Brady here sees them. Don’t you?”

Blood rushed to my face, and I nodded. Beverly gave me an appraising look, like she wasn’t sure what planet I’d materialized from.

“You’ve told me all the stories, Mrs. Edwards.”

“They’re more than stories,” said Granny.

“Sorry, that’s not what I meant. I believe all this stuff is happening, but there’s just…” Beverly trailed off, absently flipped through a few of the pages on the tabletop, as if the secrets of the universe might suddenly reveal themselves.

“Uh huh,” said Granny. “That’s where we get caught up, isn’t it? Just. That’s where our strictly materialist view of the universe falls apart.”

“I just need something to hold on to,” said Beverly.

“That’s the trick, ain’t it?”

Shirley drifted from underneath the table like silver smoke, her swirling surface capturing sunlight from another world. Her smile was mischief, and her eyes burned blue. She wanted me to follow. Shirley was restless; she never liked to remain in one place for long unless she was listening to me read. Books always calmed her. Rooted her in the world. I was the same way. I could burn away long hours without moving, so long as there were other places for me to visit in the pages of a book.

Never squirming, never impatient.

Other places always seemed better than wherever I was.

The flavor of conversation between Granny and Beverly was the same as always, so when Shirley issued the call to adventure, I followed. Crawled on all fours like a coyote sniffing at her trail. She moved across the kitchen linoleum like fog creeping across the face of the world, escaped the room and advanced down the hallway. Moving, eventually, under the closed door that led into Granny’s den. My bare hands and feet slapped against the floorboards as I followed. The wood was stained with something dark, and smelled like animals had lived here long ago.

A ghost I’d named Glen waited at the doorway. Might be he was standing guard, but I couldn’t know his motives. I wasn’t allowed in Granny’s den alone. But I was determined to follow Shirley, find out what she was up to. Glen was the ghost of an old cowboy with a crushed and weathered hat; he was nothing but bones inside his musty suit. Sometimes he wore a drawn, fretful face, wrinkled and ashen, but today he revealed only his gray, pitted skull, half his teeth fallen out and cracks radiating out from one eye socket like rays from the noonday sun. Shadows ruled the hallway, and he drew form from the darkness, appearing almost substantial. His jaw opened and closed with a sound like a cinder block dragging over concrete. Whatever he wanted to say, I wasn’t listening. I reached through him, turned the glass-handled doorknob, and proceeded into the den.

The room Granny called her den was a study, just off the hallway near the front entrance to the house. A cracked brick fireplace dominated one wall, mouth black and choking out the old scent of mesquite ash. Bookshelves crowded the other walls, overflowing with titles like The Kybalion. The Secret Teachings of All Ages. The Book of Lies. All manner of seductive-sounding volumes that drew my young self in like bugs to the porch lights. I had free run of Granny’s bookshelves, apart from those in her den. I would not read these books until much later, when I was older, and seeking insight into my grandmother’s thinking, there at the end of her life. I can’t say it made much of a difference. Questing for any true answer was folly, though it took me decades to learn that.

Stuffed in with the books were file folders and yellow notebooks full of Granny’s neat handwriting. Stacks of generic white cassette tapes with labels like Little Girl Ghost, Jumping on Bed. Snyder, TX 1972 and Interview #2 with Mrs. Mabel Starch / Plainview Prairie Beast Encounter. Melted candles and grinning crystal skulls. Wooden boxes carved with smiling suns and sleeping moons. Shirley rested a hand on top of one of those boxes, smiling dreamily. Her intention clear. Summer sunlight tried to intrude through the room’s lone window, but tan lace curtains and layers of West Texas dust held it at bay. What light existed in the room was golden and soft. Ghost light. Perfect shading for Shirley to take form. Unseen winds pulled at her calico dress. Her fingers clutched at the box, like she was trying to lift it herself. I didn’t question her. I met her hopeful stare and nodded. Snatched the box from the shelf and held it in my tiny hands.

I climbed into the swivel chair at Granny’s big oak desk, sat the box on top, careful not to disturb anything. Not to leave evidence of my trespass. The desk was littered with scraps of paper, mostly letters from people who sought out my grandmother for her advice on the supernatural. A few photos lay scattered about. Blurry images of supposed ghosts, and one that looked like a canine jowl streaking red through thick sagebrush. That one was paper clipped to a handwritten note claiming an encounter with the Chupacabra.

Normally these photos would have drawn me in; they weren’t among those Granny had shown me before. But the wooden box held the promise of unknown treasure, and Shirley clung cold against my back, obviously eager for me to open it. When I did, I found more photos. A couple dozen of them, bound in a fat rubber band. Every one of them taken inside Granny’s house. I heard that cinder-block scrape again, and realized Glen had joined us. He stood right behind me, snared by the same curiosity that held Shirley. The same curiosity that held me.

I fumbled off the rubber band. Laid the photos out.

The shooting locations were instantly recognizable. Granny’s upstairs bedroom. The kitchen, in the corner where the wobbly breakfast table stood. The formal living room, in front of the great brick fireplace. Even a few in the bathroom. Every photo taken right here in Granny’s house; every photo filled with ghostly apparitions. None of the ghosts appeared on film as clearly as they did to my waking eyes, but a few were substantial enough that I recognized them as my friends. One photo captured the old woman I’d named Lady Pecan Tree, standing beside the bed in my room, staring out the dormer window as was her habit. Blue and shimmery and transparent. Another photo showed Glen in the front living room, worn hat tipped forward to cover most of his missing face. Ephemeral hands locked together in worry. I kept flipping through the photos, found one of myself, very much alive, standing in front the towering bookshelves in the library. Some of the photos were older, but Granny took this one. Shirley stood beside me, both of us staring at the camera, like we were posing together. And I suppose we were. Shirley and I were fast friends, no matter the distance that separated us. No matter how much she wished me dead, so we might play and read together for eternity.

The ghosts at my back remained cold and still.

None of these photos were remotely frightening, and as I continued to examine them, I wondered why Granny held this particular batch in reserve.

Then I came to the last photo in the pile.

It was taken in the entryway, the camera eye facing the front door. A stained glass window dominated the top half of the door; it showed a stylized reproduction of an old-time cattle drive, beeves lumbering across the vanished prairie, cowboys on horseback, herding them ever onward. Sunlight stampeded through the glass, spilling reds and greens and golds across the floor and the walls. Bathed in that sunlight was the ghost of a man, arms crossed and grinning. So striking was the image, that if not for the way the sunlight passed through him, I might have mistaken him for a visitor to the house, waiting by the door to leave. He wore a pair of green coveralls, pants legs tucked into tall boots. His gray hair was thin and neatly combed, and a few days’ worth of stubble grew on his chin. His green eyes shone with otherworldly light. They stared at the camera. Stared at the photographer. Stared at me.

It was my grandfather.

Five years dead.

Granny, it seemed, had good reason for her secrets.

SUMMER IN THE HOUSE OF THE DEPARTED, the new novella from Josh Rountree.